Innovation Lives Outside of the Comfort Zone.

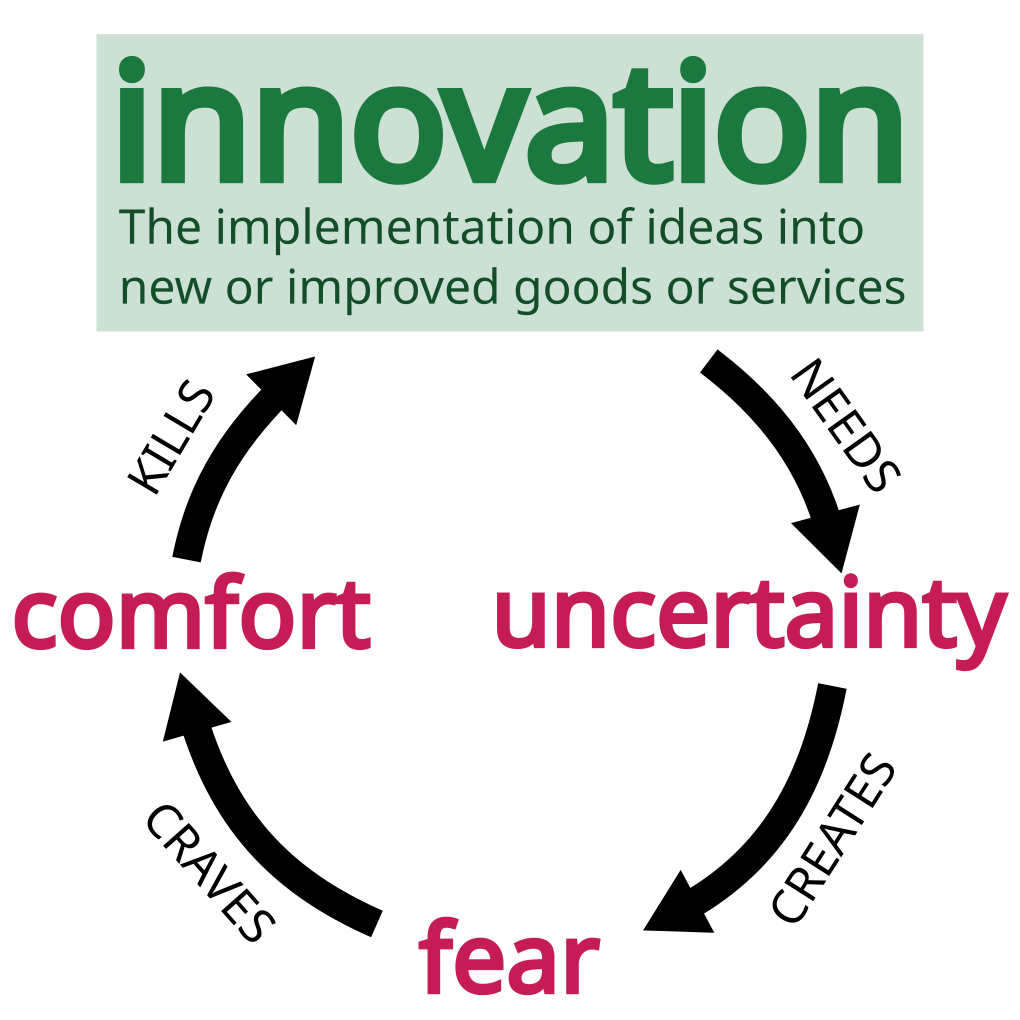

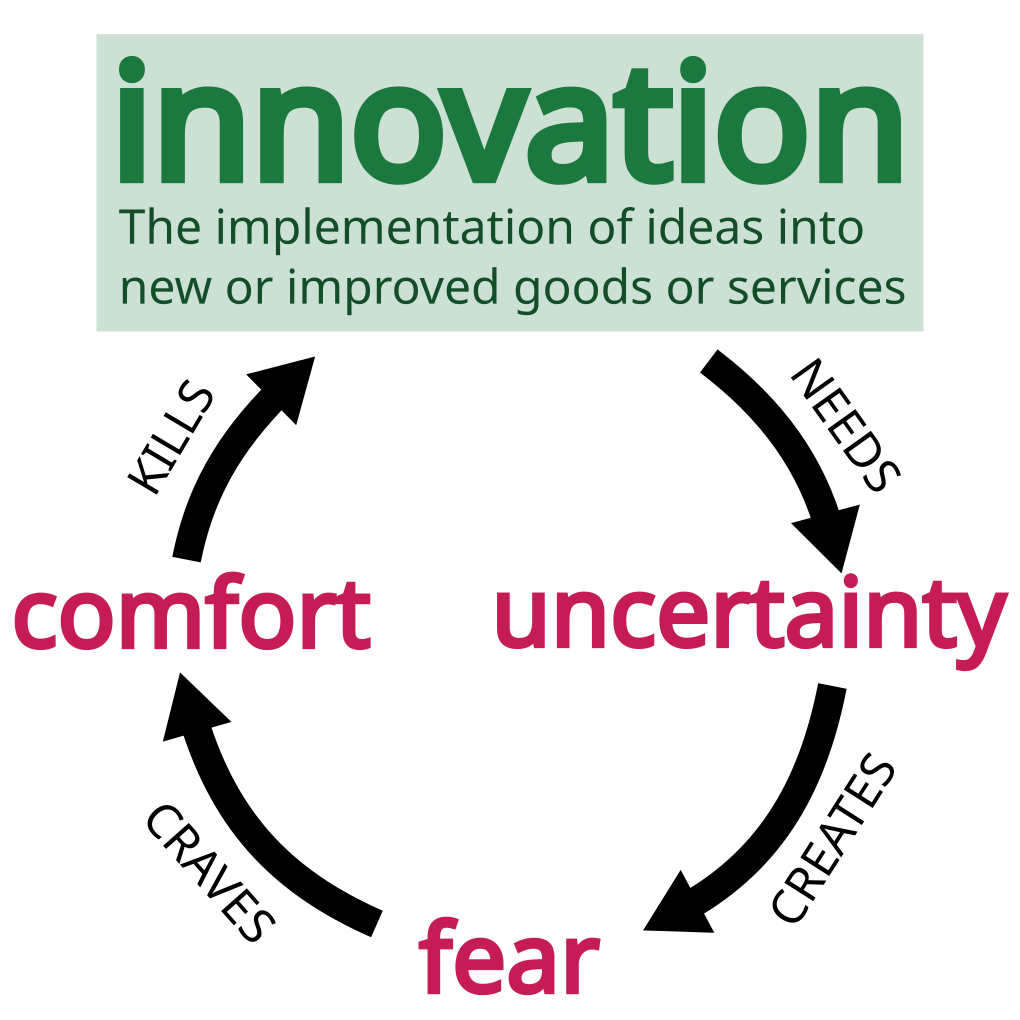

Innovation efforts can fall short not only due to poor strategy or execution, but also human nature. Disruptive innovation demands uncertainty, but uncertainty triggers fear, driving us back to the comfort of the familiar, which kills innovation. This article explores the science behind how innovators unknowingly sabotage progress—and how to break free from the cycle.

Innovation Lives Outside of the Comfort Zone.

Innovation efforts can fall short not only due to poor strategy or execution, but also human nature. Disruptive innovation demands uncertainty, but uncertainty triggers fear, driving us back to the comfort of the familiar, which kills innovation. This article explores the science behind how innovators unknowingly sabotage progress—and how to break free from the cycle.

Academia and industry pour billions into innovation every year, chasing the next breakthrough. Yet, despite all the resources, many of these efforts stagnate in incremental improvements. The problem isn’t always flawed strategy or execution. More often, it’s how humans respond to the uncertainty that comes with disruptive innovation. Uncertainty triggers fear, which pulls us toward the comfort of the familiar. But comfort is where innovation goes to die.

This article dives into the science behind how innovators, often unknowingly, get in their own way. From cognitive biases to brain chemistry, we’ll explore why humans resist the very thing innovation requires, and how to break free from the cycle.

Innovation Needs Uncertainty

Innovation, by definition, is the creation of something new—whether an idea, method, or product. But novelty comes with uncertainty and risk. Rather than avoiding it, innovators must embrace uncertainty as a core driver of progress.

Organizations that succeed long-term do so by continuously experimenting, learning, and adapting. Research on organizational learning shows that companies balancing exploration (testing uncertain, new ideas) and exploitation (refining proven ones) are more adaptable and resilient [1]. This ability to navigate uncertainty directly correlates with stronger innovation, better market performance, and long-term survival [2].

Nowhere is this clearer than in the startup world, where progress is built on rapid iteration. Successful entrepreneurs don’t seek certainty; they embrace trial and error, testing ideas, gathering feedback, and pivoting as needed. The Lean Startup approach, for example, embeds uncertainty into the process, recognizing that progress comes from continuous experimentation rather than rigid planning [3].

Yet, the European innovation ecosystem faces persistent barriers in technology transfer, preventing academic breakthroughs from becoming market-ready solutions [4]. While uncertainty fuels discovery, it also introduces risk—something institutions, businesses, and individuals often seek to minimize.

Uncertainty Creates Fear

Despite the growing recognition of its role in driving innovation and progress, thriving in uncertain conditions is easier said than done. Our biological and psychological makeup makes uncertainty inherently uncomfortable. When faced with uncertain situations, the body triggers a stress response [5]. At the same time, our brain’s fear circuitry—particularly the amygdala—becomes activated [6]. In fact, research from 2023 suggests that anxiety disorders may stem from an individual’s intolerance of uncertainty [7], illustrating just how deeply rooted our aversion to uncertainty can be.

Studies suggest that within academic circles, commercialization pressures can feel at odds with traditional academic values, raising concerns about research integrity and openness [8]. Many academics, particularly early- and late-career researchers, hesitate to disclose commercial activities for fear of harming their reputation within the research community [9]. As a result, promising innovations often remain within the lab rather than reaching real-world impact.

Fear Craves Comfort

Fear of the unknown often leads to decision-making that prioritizes comfort over opportunity. Research shows that people irrationally reject uncertain options—even when they offer higher potential rewards—just to escape ambiguity [10]. In some cases, people even prefer anticipating a negative outcome rather than dealing with the stress of uncertainty [11]. Avoidance becomes a coping mechanism, even when it leads to worse long-term consequences.

Cognitive biases reinforce this behavior. Loss aversion makes potential losses feel more painful than equivalent gains feel rewarding [12], while status quo bias pushes individuals to maintain familiar situations, even at the expense of better outcomes [13]. Over time, habitual behaviors become ingrained in neural circuits, making it easier to default to routine rather than embrace change [14].

The result? People and organizations cling to what’s familiar, missing opportunities for innovation. To break free, we must challenge our instinctive preference for predictability and actively seek discomfort as a path to growth.

Comfort Kills Innovation

To innovate, we must think creatively. Yet, research suggests that uncertainty reduces our ability to recognize and generate creative ideas [15]. When faced with ambiguity, we instinctively turn to familiar solutions rather than exploring new possibilities. This tendency to avoid creativity in uncertain conditions stifles innovation, preventing breakthroughs before they even begin.

The risks of comfort-driven stagnation are well-documented. Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma (1997) highlights how successful companies often fail to innovate because they become too reliant on existing business models [16]. Fear of disrupting their own success leads them to resist change, leaving them vulnerable to more adaptable competitors.

Resistance to change is one of the biggest obstacles to innovation. Studies show that nearly 70% of innovation initiatives fail due to organizational resistance [17]. The preference for routine keep individuals and companies locked in the status quo, making them less likely to adopt new ideas—even when those ideas are necessary for long-term success. In a world that demands continuous adaptation, clinging to comfort is often the very thing that leads to failure.

Innovate by addressing human nature

rue innovation doesn’t happen in the comfort of certainty. Whether in startups, corporations, or academia, the most impactful breakthroughs emerge when we deliberately engage with uncertainty. A recent review highlights two key strategies for overcoming our fear of the unknown [10]:

- Reframe uncertainty as an opportunity. Rather than seeing ambiguity as a threat, innovators can train themselves to recognize its benefits—heightened focus, increased creativity, and expanded problem-solving abilities.

- Start small to build resilience. Taking incremental risks—experimenting with new ideas, seeking unfamiliar perspectives, or expanding professional networks—helps develop the adaptability needed for bigger, more disruptive innovation.

The most successful innovators don’t just tolerate uncertainty—they use it as fuel. The key isn’t eliminating discomfort but rewiring how we respond to it.

So ask yourself: What uncertainties are you avoiding today? What small risks could help you step outside your comfort zone?

Citations:

- J. G. March, “Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning,” Organization Science, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 71–87, Feb. 1991, doi: https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71.

- O'Reilly III, Charles A., and Michael L. Tushman. "Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future." Academy of management Perspectives 27.4 (2013): 324-338.

- A. Maurya, Running Lean: Iterate from Plan A to a Plan That Works. Sebastopol, CA, USA: O'Reilly Media, 2012.

- M. Draghi, "The Future of European Competitiveness: A Competitiveness Strategy for Europe," European Commission, 9 September 2024. [Online]. Available: here. [Accessed: 13-Feb-2025].

- De Berker, Archy O., et al. "Computations of uncertainty mediate acute stress responses in humans." Nature communications 7.1 (2016): 10996.

- Hsu, Ming, et al. "Neural systems responding to degrees of uncertainty in human decision-making." Science 310.5754 (2005): 1680-1683.

- Brown, Vanessa M., Rebecca Price, and Alexandre Y. Dombrovski. "Anxiety as a disorder of uncertainty: Implications for understanding maladaptive anxiety, anxious avoidance, and exposure therapy." Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience 23.3 (2023): 844-868.

- Caulfield, Timothy, and Ubaka Ogbogu. "The commercialization of university-based research: Balancing risks and benefits." BMC medical ethics 16 (2015): 1-7.

- Silvestri, Cleo, Markus Perkmann, and Paola Criscuolo. "Science Impact vs Scientific Purity: Why Academic Scientists May Not Publicly Reveal Their Commercial Activities." Available at SSRN 5085483.

- Alquist, Jessica L., and Roy F. Baumeister. "Learning to Love Uncertainty." Current Directions in Psychological Science 33.6 (2024): 355-360.

- Barasz, Kate, and Serena F. Hagerty. "Hoping for the worst? A paradoxical preference for bad news." Journal of Consumer Research 48.2 (2021): 270-288.

- Schmidt, Ulrich, and Horst Zank. "What is loss aversion?." Journal of risk and uncertainty 30 (2005): 157-167.

- Samuelson, William, and Richard Zeckhauser. "Status quo bias in decision making." Journal of risk and uncertainty 1 (1988): 7-59.

- Delude, Cathryn M. “Brain Researchers Explain Why Old Habits Die Hard.” MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 19 Oct. 2005, news.mit.edu/2005/habit?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 24 Mar. 2025.

- Mueller, Jennifer S., Shimul Melwani, and Jack A. Goncalo. "The bias against creativity: Why people desire but reject creative ideas." Psychological science 23.1 (2012): 13-17.

- Wikipedia Contributors. “The Innovator’s Dilemma.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Apr. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Innovator%27s_Dilemma.

- “Overcoming Resistance: Best Practices for Innovation Implementation.” Join the Collective, 21 Nov. 2023, www.jointhecollective.com/article/overcoming-resistance-best-practices-for-innovation-implementation/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 24 Mar. 2025.